How many philosophers does it take to screw in a light bulb? There is no clear answer to that yet, because they are still discussing their moral position regarding artificial illumination.

And what if the world started spinning faster and we all lost our balance, as suggested by Tommy Roe in his 1968 song Dizzy: “My head is spinning, I’m going around in circles all the time…” (Tommy will soon be 82, so I hope that hasn’t become true by now.) Would such an event turn philosophy completely on its head? It’s a three-pipe problem, or a one-philosopher problem, if he has his head screwed on the right way and the light bulb in his brain is working.

I’d pick science over philosophy any time. Well, most of the time, at least. Science does have its curious side. For example, the first scientist may never have existed at all. Like Homer (the Greek one) he is likely to have been a composite figure who was credited with great achievements while really achieving nothing. So an early version of the other Homer, then. As for other boffins in the running for the title of First Egghead, frankly, many of them weren’t what they were cracked up to be. Euclid was most likely a team of mathematicians. Ptolemy misguidedly placed Earth at the centre of the cosmos. Even Einstein thought the universe was static, tsk, tsk. Didn’t he know about the speed of light?

Limited by their resources, early scientists had to indulge in guessing games, whereas nowadays scientific results rely on experiments to prove a theory, the scientific word for a guess. Writers like to make things up, scientists like to know how things work, and artists splash paint on things when they have been at the absinthe. I believe many artists have to borrow money from church mice, at least until they die, when their pictures become worth a fortune and they could repay the mice in whatever the collective noun is for cheese boards. A smorgasbord, perhaps.

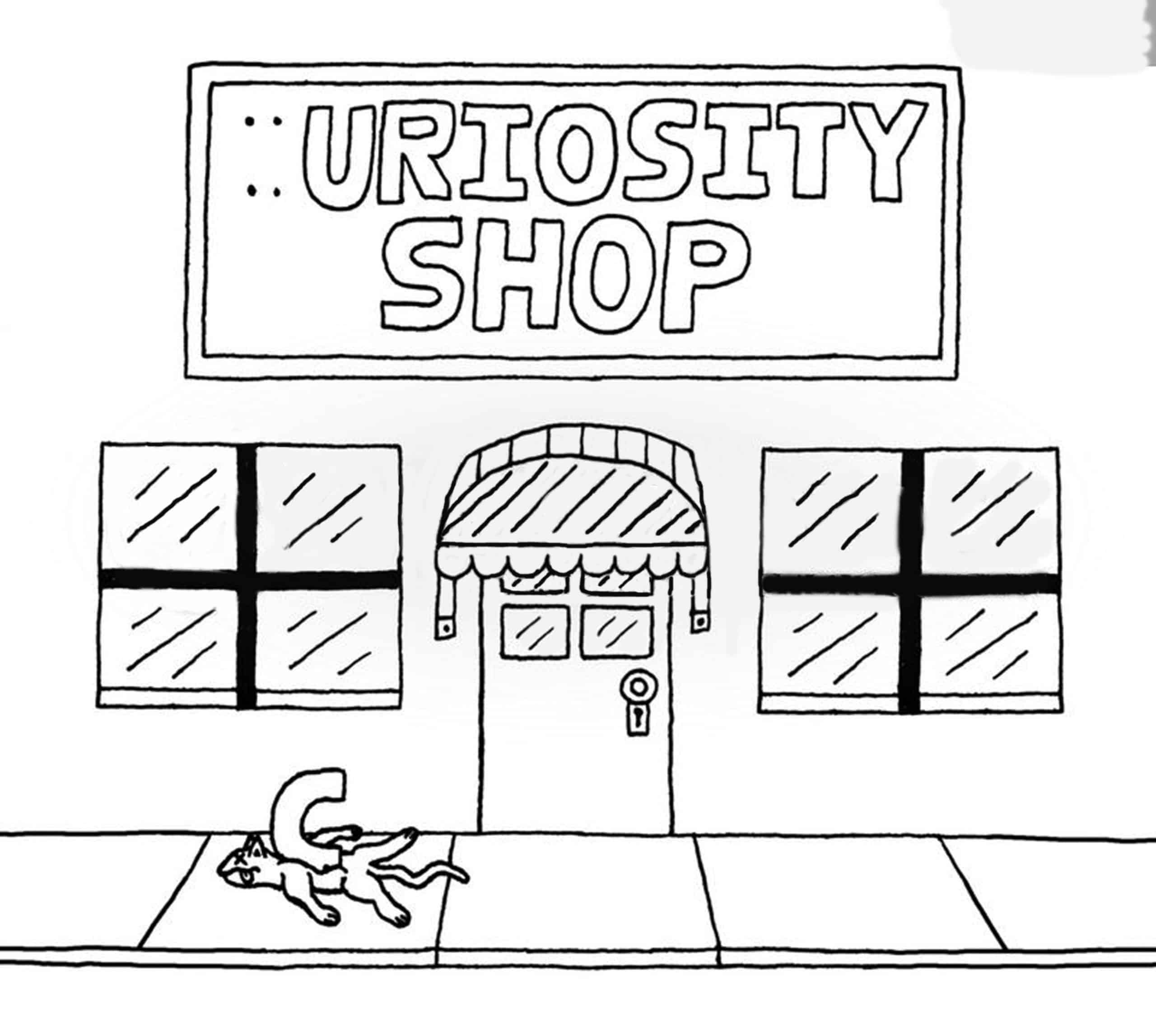

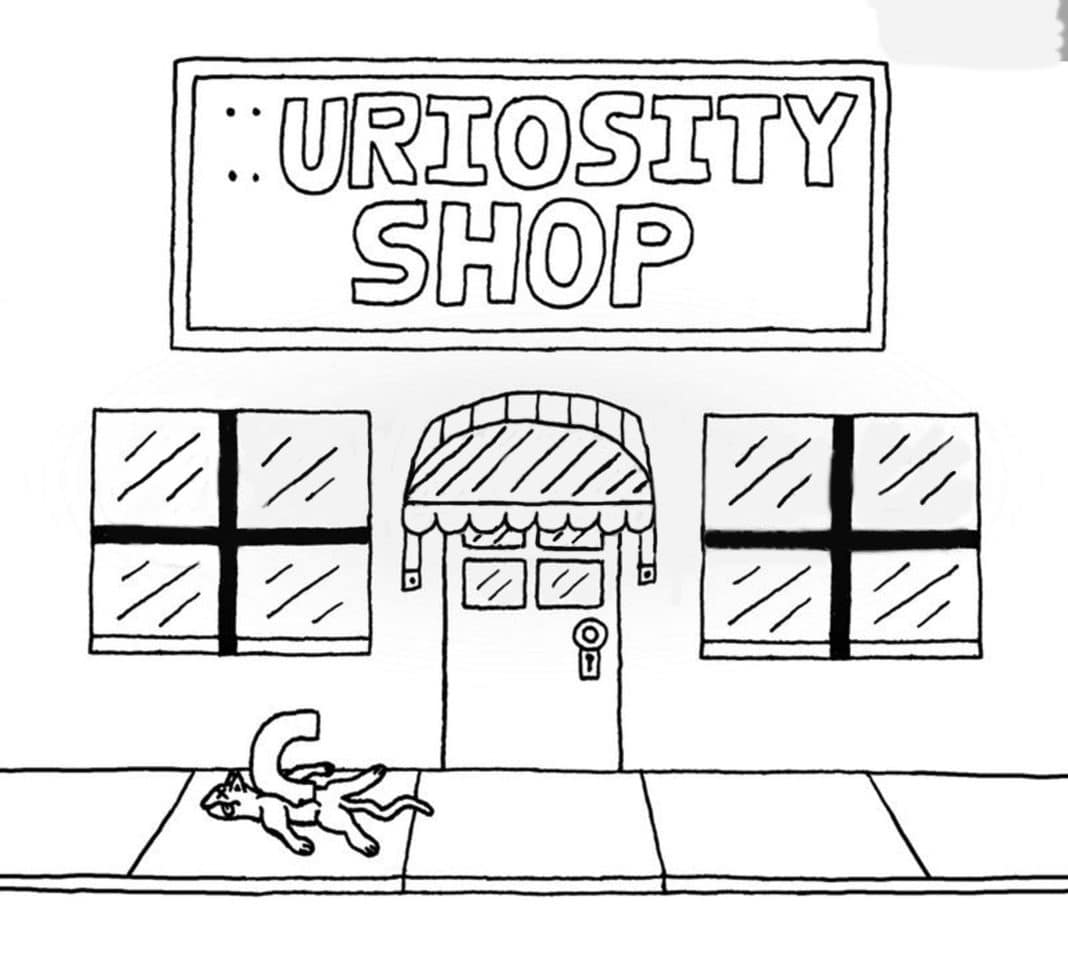

One of our main advantages over the rest of the animal kingdom is curiosity. It is no accident that NASA’s car-sized Mars rover was named Curiosity, when it was searching for signs of life on the red planet. Curiosity supposedly kills cats, so perhaps they shouldn’t ask so many questions. Scaredy-cats should cross roads carefully, especially if 8 of their 9 lives have already crossed the great divide between pavements.

But without curiosity, Edward Jenner might never have tried infecting his gardener’s son with a mild virus to produce immunity against a deadly virus like smallpox. And the rest is history. And for once we have learned from it, and are only too glad to repeat it. The cure for boredom is curiosity, and fortunately there is no cure for curiosity.

Or sometimes unfortunately. It may be why we went to the moon (or some of us did) but it also makes us touch hotplates when warned they might burn us. It is why children start smoking cigarettes, or worse. Curiosity makes us act as if horses won’t throw us, white-water rafting won’t drown us, and love won’t break our hearts. It even makes us wonder if cats will come when we call them. For a small fee, I can provide answers to all those questions.

As the Earth goes on turning — at its usual rate — we could all be forgiven for feeling, in the words of Alice in Wonderland, that life is becoming “curiouser and curiouser,” in a world where normal rules no longer seem to apply. Do you ever wonder why? I do, and am puzzled when people talk about ‘idle’ curiosity. Mine, like yours I hope, is working all the time.

David Aitken