Can I ask you to please settle down, as the lecture is about to begin. I know those chairs aren’t very comfortable, but I’m hoping they will help you to stay awake. Or some of you anyway. One or two would be nice. Or at least the person in the front row with all the pens in his jacket pocket.

A virus, you will be happy to learn, does not possess a brain or anything remotely similar to a brain: viruses are not sophisticated thinkers. You’ve probably met someone like that, haven’t you? In your Boxing for Beginners class, perhaps.

Viruses are smaller than bacteria and there is zero possibility that a single virus could develop little grey cells, far less compose a symphony or be attractive to another single virus, even during a speed-dating encounter.

However, owing to their ability to mutate and become resistant to drugs — and a vaccine is a drug — some viruses are able to give our brains a run for their money. The recent strain of Omicron is one such blowhard sprinter, quick out of the blocks and eager to show our various vaccines a clean pair of heels, or an unclean set of spikes.

Before we drown in mixed metaphors, let’s hope all variants fall at the first fence and run out of puff long before this marathon is over and our virologists collect their gold medals. Here endeth the strained analogy.

Many predators attack humans only when they feel threatened, or afraid, or when we encroach on their territory. Saltwater crocodiles, commonly called ‘salties’, are an exception to this rule; they have been known to knock Land Cruisers off roadways with one swipe of their tails, and are not fastidious when choosing food. In their unfeeling viciousness and speed of attack, salties resemble our new arch-enemy Omicron, the Hannibal Lecter of the virus world. (To be fair to salties, they often spend most of the day loitering in pools or basking in the sun, at which point they could easily be mistaken for innocent retired expatriates.)

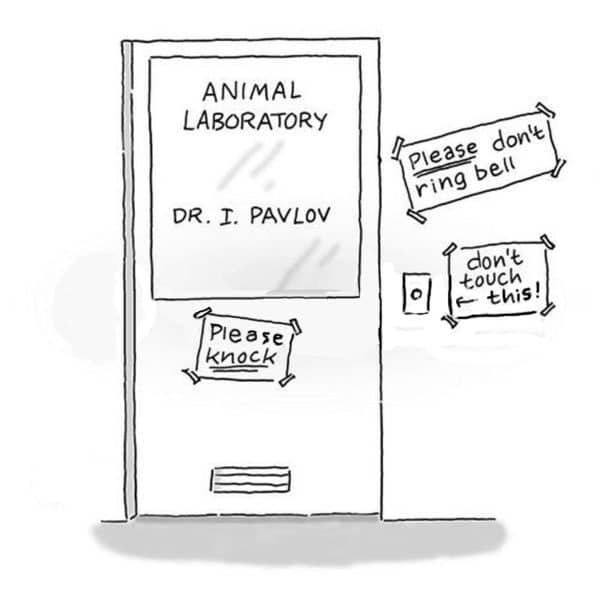

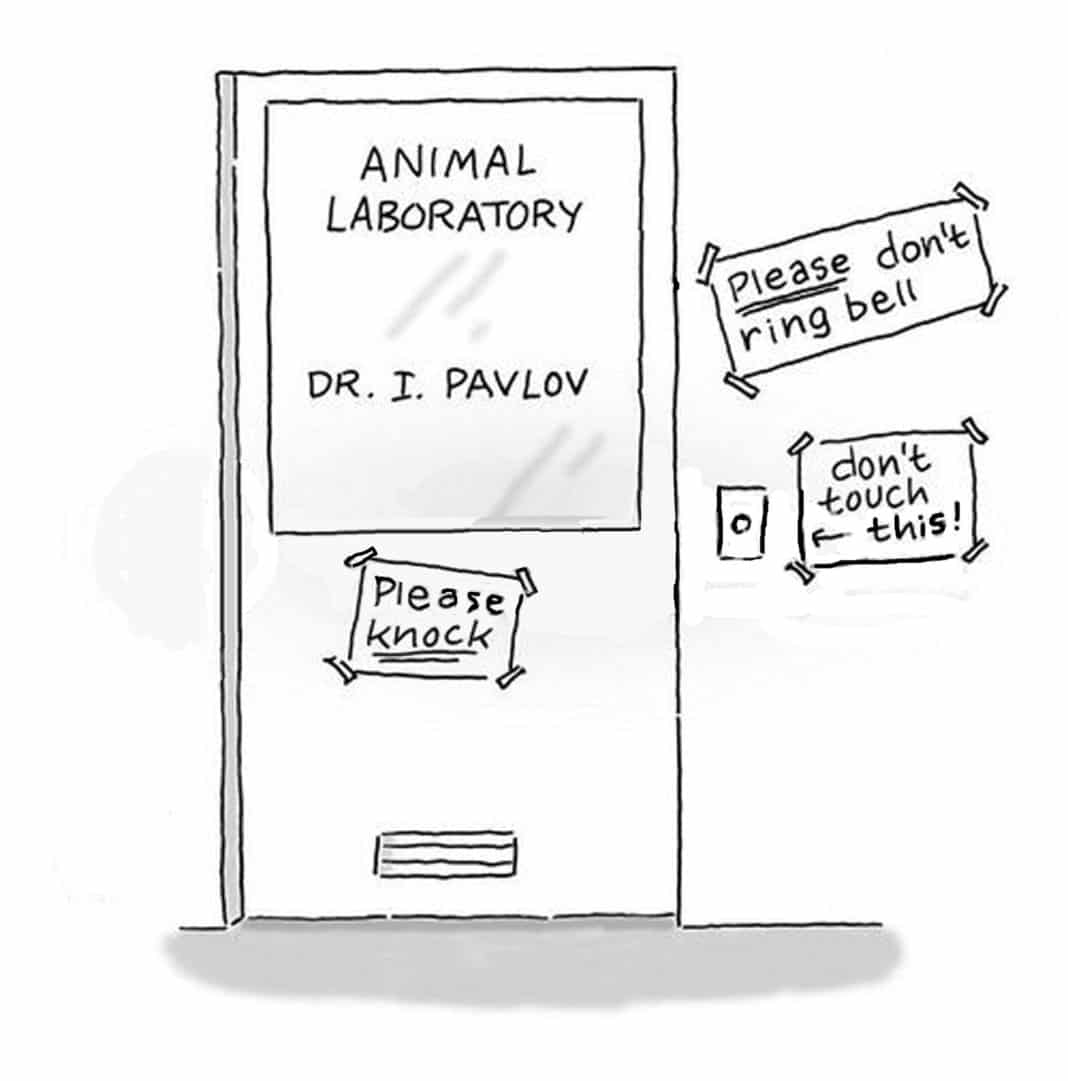

Pavlov proved through experiments with dogs that a neutral stimulus like a bell could be made to produce the same response as a powerful stimulus such as food. And that sentence, basically, won him a Nobel Prize. I wish I had known it was as easy as that, I would have bought a dog.

Pavov showed that if you nudge — or inoculate — a body often enough, it learns to remember — or become immune. It’s the story of Covid in canine form! I know that if you were to place a tray of food in front of me, then fire a starting pistol, I would wolf the meal down in the service of science. Provided I liked the food involved — did Pavlov ever take that into account?

Children, whose fear of corona viruses receded when told they were immune, began to exercise their natural curiosity, asking such questions as, “Do viruses have wings? If not, how do they navigate between their victims? If they run out of energy in mid-air, do they crash-land, or become a parachute-variant?” That boy’s father must have been in the SAS.

One of the easier inquiries put to me was “How did Omicron move so quickly from one country to another?” to which I, of course, replied, Smoke gets in your eyes, no, I explained that it probably went by plane like many of us used to do. Except Omicron travelled free, and we were the ones who paid the price.

I hope you enjoyed the lecture and now know the answer to my implied question — you remember, the one about which of us have brains? People who get vaccinated do, is the correct answer. And you can bet your life on that.