By John McGregor

Part Two

In 1865, two hundred years after Rob Roy reigned, a young Scot named John McGregor and his wife Janet bravely sailed to the other side of the earth. Together with their baby son on the good ship Resolute from Glasgow to New Zealand they began a new life, as far from their roots and family as is humanly possible. Life was tough for those early settlers, especially when they arrived amid a very harsh winter. The first house they built was soon smashed to pieces by a violent storm. Long hours of hard back-breaking work, and improvisation was essential to survive. This John McGregor, my father’s great grandfather tragically died in a mining accident at the age of only thirty-seven after fathering seven more children. In the ten years from landing in Auckland he had built the family a substantial home and a life for them in that young country, which his resourceful children then maintained. There is a family book written on our history from that period*.

This austere background of the New Zealand settlers, starting from nothing was handed down through the subsequent generations. Dad told me how as boys they built their bikes from re-cycled bits, illustrating his wonderful gift of improvisation. In the early eighties I moved into a modern home and decided on a new kitchen, although the existing one there was quite adequate. In the space of two weekends Dad dismantled our old one and re-assembled it in a completely differently shaped kitchen in my parents’ house. It looked as new and functional in theirs as our new one did in ours.

One of Dad’s lifetime hobbies was clocks, and I inherited his love of them, I have them all over my house. One of my most treasured possessions is a clock (pictured) that Dad made from the circular control column of the Boulton-Paul Defiant he crashed in. It is small but quite heavy and on the round handle of the column it has a safe/fire button which was used to action the forward machine-gun. After the war Dad made a circular brass face for the clock, with black hands. It has pride of place on my mantelpiece, and keeps perfect time. It always reminds me of my Dad, my hero.

In the four years before his plane crash in West Africa Dad had packed in a great deal.In 1941 as an eighteen year-old good, loyal Antipodean he had left his widowed mother and siblings to sail from Auckland to the UK to join the Royal Navy. In Portsmouth he passed an intensive course to be offered a commission as a pilot in either the RAF or the Fleet Air Arm. Being a Navy man it was no contest. My father then fulfilled a promise to his NZ boyhood pal, to contact the mate’s penfriend while in the UK. Dad did much more than requested, he married my mother in 1943 and my big sister was born the following year. There being a war on, immediately after the birth Dad was posted to West Africa for the last two years of the war, where he was then demobbed straight back to New Zealand.

Following the end of the war, Mum and my sister joined Dad in Auckland. But through a combination of poor work prospects there and serious family illness in the UK they returned in 1948, I was born the following year. After various jobs, Dad eventually went back to fly in the Navy for four more successful years. The first ten years of my life were always on the move, I went to seven different schools and my big sister thirteen.

Am I my father’s son? Cossetted in upbringing in comparison to my father and our predecessors, after a promising start to my adult life and with a young family and a good job I experienced a few difficult years in my early thirties. An acrimonious and costly divorce left me with no capital, compounded with leaving the company I loved after eleven successful years, only to make a disastrous sideways career move. Alone in a scruffy flat, only seeing my children at weekends, unhappy in my work, drinking too much and with several thousand pounds of family debt hanging over me I was at a low ebb in my life. But what was my name? Eventually I snapped out of my situation: this time I made a good career choice, stopped drinking, paid off my debts, and re-married. Subsequent years proved much happier and more productive. I am on very good terms with my two children today and have four lovely grandchildren.

In an incredible echo of our great grandparents’ emigration from Scotland, over a century and a half later my own son took his wife and baby daughter to live in New Zealand in 2004. Lower wages in NZ and family illness meant that the young family returned to the UK after three years, wiser and much more experienced with life. My son displays his grandfather’s characteristics: mental strength, integrity, resourcefulness: he invites respect from others.

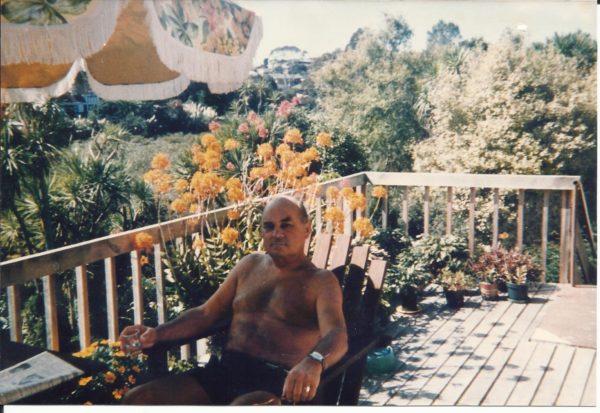

Dad tragically died in 1988, aged only sixty-six. He had retired, fit and healthy eighteen months earlier, with a richly-deserved period of his life to look forward to. Almost immediately, a growth in his cheek revealed throat cancer, a legacy of Naval pipe smoking. It was the beginning of the end. Still demonstrating his customary mental and physical strength, between intense periods of debilitating radio and chemotherapy treatment Dad took Mum back to New Zealand for five months. Here he was re-united with his family and old friends he had not seen for forty years, before returning home to the UK to sadly lose the one battle he could not win. The mark the man left on me was a responsibility for myself and to others, a self-reliance, a hugely practical commonsense attitude to life that Dad always displayed. There is still much to do to emulate my father, in truth an impossible task, but I’m trying – what’s my name? McGregor!

*Leslie Wylie McGregor, SEED OF A COUNTRY, 1988 , Privately Published

PS My Dad’s personal account of his aircraft crash in the West African forest in 1944 and how he survived is too large for a newspaper article. But if anyone would like to read it and see the pictures please contact me by e mail on mcgregorjaw@hotmail.co.uk